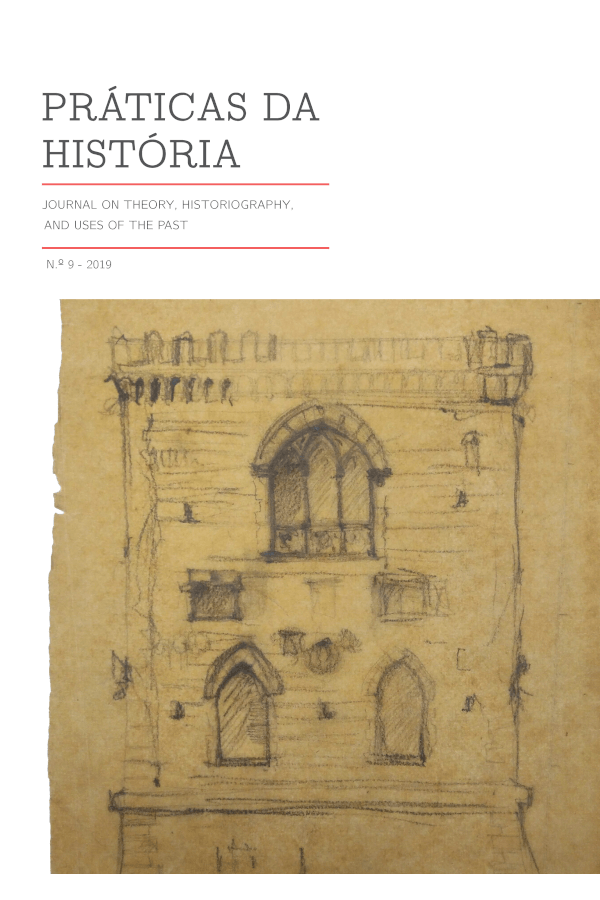

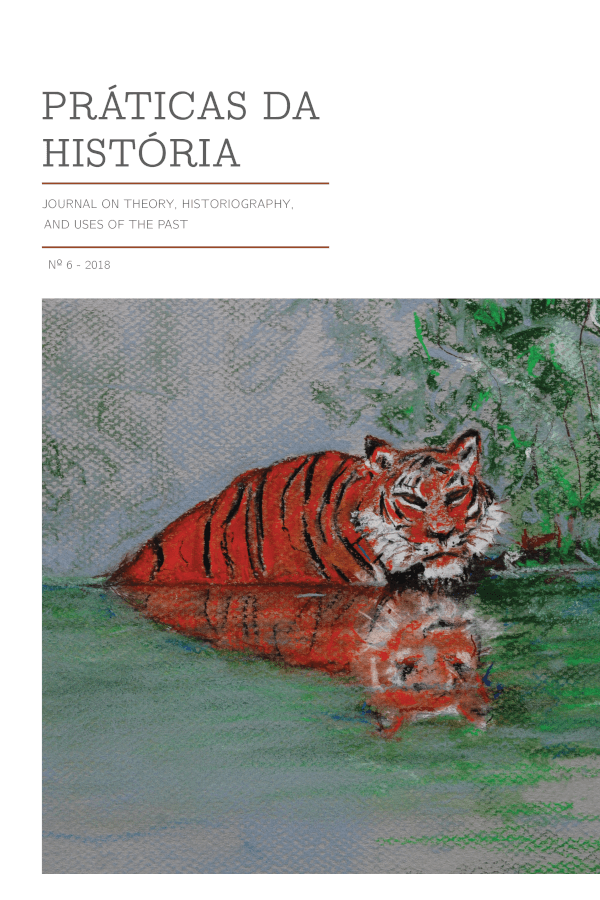

Práticas da História Nº 3

Mar 7, 2018 | 2016, Edições, Revista Práticas da História

Práticas da História – Journal on Theory, Historiography and Uses of the Past

- 2016

- Número 3

- ISSN: 2183-590X

- Tema: “The archive and the subaltern” – Coordenado por Carolien Stolte e António da Silva Rego

Editorial:

This special issue takes inspiration from a series of events surrounding Dipesh Chakrabarty’s visit to Leiden University in October 2015. Especially thought-provoking was the Faculty Roundtable entitled ‘Minor Archives, Meta Histories: Rethinking Peripheries in the Age of Global Assemblages’. Together with Nira Wickramasinghe, Ksenia Robbe, Wayne Modest, and Ethan Mark, Chakrabarty discussed the potential of the ‘minor mode’: scholarship that seeks to give voice to the marginalized, foregrounds history’s ‘unlikely subjects’ and critiques the larger historiographical frames that rendered them invisible in the first place. Questions that drove the roundtable were how we might use micro-voices, -histories, and –archives to articulate different conceptions of the global and of global history; how they might help to imagine a post-national historiography in the Global South; but also where we might look for the appropriate sources for such histories. In other words: what is the archive of the minor?

A full transcript of the roundtable is included with this issue, in which the speakers touch on issues ranging from the interpretation of Australian Aboriginal songs, to discursive power imbalances within the Global South, to the ways in which scaling up – even to the planetary level – can still be considered part of the ‘minor mode’. Making this roundtable available to the wider public was an initiative of António da Silva Rêgo. From that starting point we developed the idea of a dedicated special issue, for which we recruited reflections on the nature of the archive and the possible sources for writing subaltern history.

In the first research article, ‘Travellers in Archives, or the Possibilities of a Post-Post-Archival Historiography’, Benjamin Zachariah shows what the historical profession stands to gain from a more active conception of the archive. It is time, he argues, to recover from the ‘post-archival’ condition, first contracted by historians in the wake of the postmodernist interventions of the 1970s and, more pertinent to this special issue, Ranajit Guha’s influential intervention in Subaltern Studies II [Ranajit Guha, “The Prose of Counter-Insurgency,” in Selected Subaltern Studies, ed. Ranajit Guha and Gayatri Spivak, (New Dehli: Oxford University Press, 1988 [1983]), 45-85]. The archive was generalized into a state-created collection of documents, meant to reinforce the state’s own legitimacy. With the colonial archive, in this view, the statist perspective was further exacerbated. As Zachariah notes, the colonial archive was seen as a ‘repository of prejudice’, reflecting colonial viewpoints rather than historical reality. Any effort to be attentive to the way the colonial archive was constructed, to read sources critically or to compensate for the biases inherent in the archive, was doomed to failure: Guha concluded his essay by stating that even historians seeking to write from the subaltern’s point of view are distanced from colonial discourse ‘only by a declaration of sentiment’ [Ranajit Guha, “The Prose of Counter-Insurgency,” in Selected Subaltern Studies, ed. Ranajit Guha and Gayatri Spivak, (New Dehli: Oxford University Press, 1988 [1983]), 84].

Zachariah calls upon historians to join a recent historiographical trend that, while maintaining a critical perspective on the archive, can overcome some of the limiting aspects of Guha’s view of it: by seeing the archive not as a place, but as a rhetorical move – a set of sources collected and combined by the historian, driven by his or her research questions. For archivally-minded historians his conclusions will be cause for optimism: ‘the singular control over history and memory attributed to ‘the’ archive has never existed. We invent an archive every time we have a question to answer; and then someone reinvents the archive in the service of a new question.’

Next, Dale Luis Menezes questions Indian nationalist discourses in Portuguese India, and the sources we need to consider these discourses critically. ‘Christians and Spices: a Critical Reflection on Indian Nationalist Discourses in Portuguese India’ illuminates the unique colonial trajectory that set Portuguese India apart from British India, and the way this has shaped a postcolonial trajectory for the region that likewise sets it apart from the Indian nationalist mainstream. Examining debates in the Konkani language press, in pamphlets and in other political writings, he problematizes the widespread understanding of the Portuguese period as one of spiritual and cultural destruction, as well as its mirror image: the problematic ways in which the region was discursively ‘made’ into an integral part of the Indian nation.

With Ruy Llera Blanes’ article, our discussion stays within the realm of archives and their representation of subaltern interests and perspectives. His contribution, too, is ultimately optimistic when it comes to archival potential, but like our other contributors, he locates this potential outside the archives of the state. In ‘A Febre do Arquivo. O “efeito Benjamin” e as revoluções angolanas’ (Archival Fever. The “Benjamin effect” and the Angolan Revolutions’), Blanes discusses the crucial importance of the archive in understanding recent political upheavals in Angola. Taking his cue from Derrida’s concept of archive fever [Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever. A Freudian Impression [first published as Mal d’Archive: Une Impression Freudienne] (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995)], he argues that Angola’s contemporary political dialectic produces a distance between hegemonic and subaltern interests in confrontation. Blanes analyzes the archive of the so-called Revu movement as a subaltern archive, and elucidates the processes through which it poses an epistemological alternative to the official narrative of the Angolan regime. This includes rendering ‘invisible chronologies’ of protest and repression visible, and the ‘recovery’ of lost memory: it offers a rereading of the history of Angola as an independent country.

Orazio Irrera concludes the research section with an article entitled ‘De l’archéologie du savoir aux archives coloniales. L’archive comme dispositif colonial de violence épistémique’ (On the Archaeology of Knowledge in Colonial Archives. The Archive as a Colonial Device of Epistemic Violence). Irrera problematizes the archive as a place of production of truth at the intersection of its epistemological

and juridico-political matrices, in order to show to what extent the archive reflects European modernity and its colonial expansion. With Benjamin Zachariah above, he notes that recent projects, both documentary and artistic, have made the archive into an object of derision, the device of an alternative history or counter-memory. Irrera argues, however, that the force of subversion revealed by these projects cannot be understood without grasping the specific type of violence that once accompanied the establishment of the archives. Referring to strategies of objectification, surveillance, and control, he shows how the archive is linked to the proces of extracting and registering knowledge. Analyzing the archive’s direct relationship to such forms of epistemic violence, he focuses on two different aspects: ‘gestures of silence’, which create discernable absences in the colonial archive, and the ways in which the colonial archive testifies to an anguish linked to discrepancies between colonial intent, and practice on the ground.

Ranging from India to Angola and from the Goan vernacular press to records of the colonial state, each contribution to this issue takes forward questions around the archive and the minor mode. Fittingly, the issue is completed by an in-depth interview with Sanjay Seth, known for his thoughtful interventions on the theory and practice of writing history, conducted by José Neves.

Carolien Stolte (Leiden University)

Outras Publicações

Pesquisa

Agenda

julho, 2025

Tipologia do Evento:

Todos

Todos

Apresentação

Ciclo

Colóquio

Conferência

Congresso

Curso

Debate

Encontro

Exposição

Inauguração

Jornadas

Lançamento

Mesa-redonda

Mostra

Open calls

Outros

Palestra

Roteiro

Seminário

Sessão de cinema

Simpósio

Workshop

- Event Name

seg

ter

qua

qui

sex

sab

dom

-

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

Detalhes do Evento

Sobre as múltiplas dimensões – histórias, processos, legados e memórias – desses eventos independentistas que mudaram a configuração da política global do mundo da segunda metade do século XX.

Ver mais

Detalhes do Evento

Sobre as múltiplas dimensões – histórias, processos, legados e memórias – desses eventos independentistas que mudaram a configuração da política global do mundo da segunda metade do século XX.

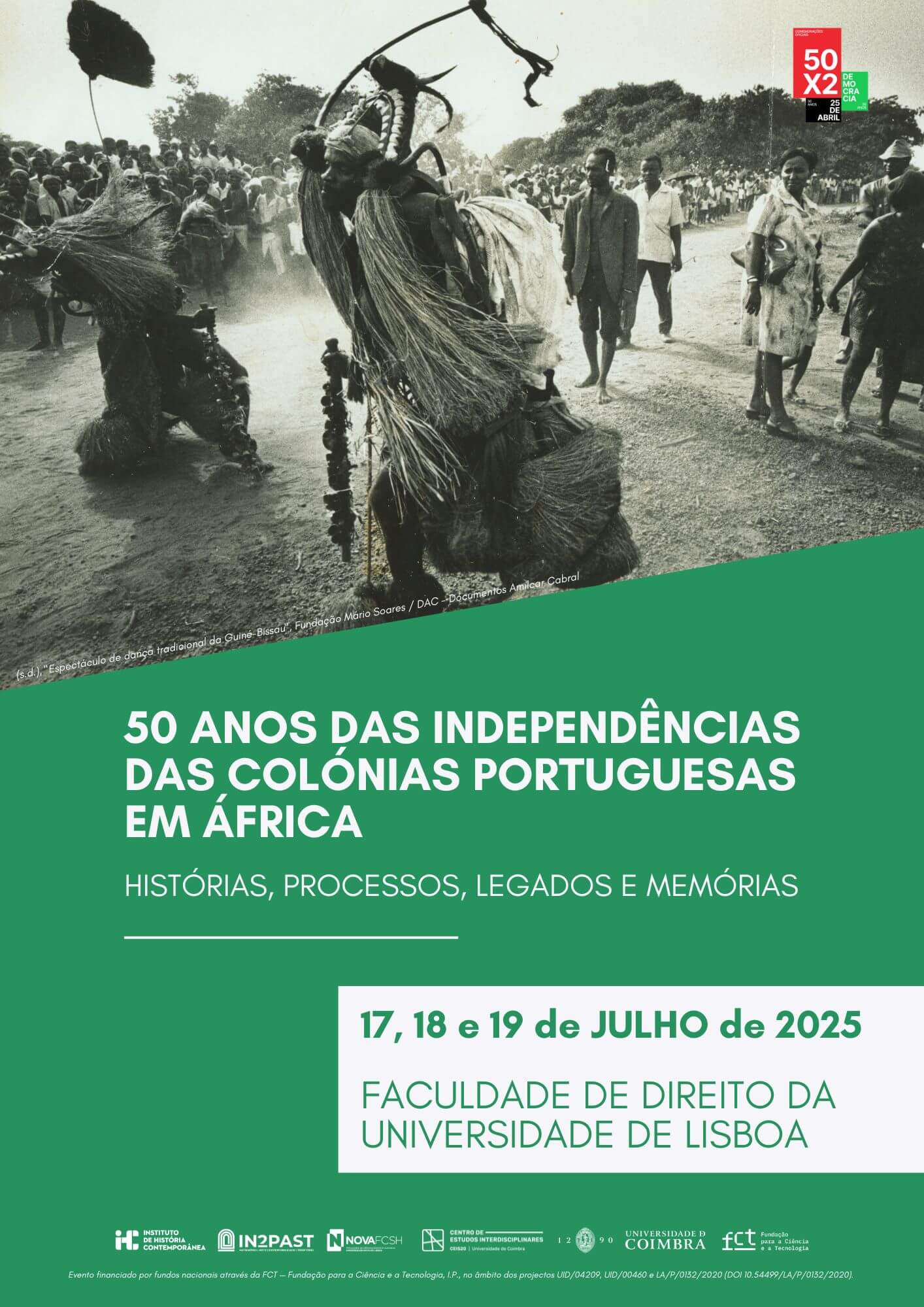

50 Anos das Independências das Colónias Portuguesas em África:

Histórias, Processos, Legados e Memórias

Em 2025, quatro antigas colónias portuguesas de África (Angola, Cabo Verde, Moçambique e São Tomé e Príncipe) celebram o cinquentenário das suas independências, vindo juntar-se à Guiné-Bissau, que dois anos antes (em Setembro de 1973), proclamara unilateralmente a existência do Estado da Guiné-Bissau, acedendo à independência formalmente a 10 de Setembro de 1974. Os processos negociais complexos que abririam as portas às independências destes territórios que estiveram durante séculos sob o domínio português não foram lineares. Assim, desde a Declaração Unilateral da Independência da Guiné (um importante precedente a nível internacional) às negociações nos casos de Angola, Cabo Verde, Moçambique e São Tomé e Príncipe, envolveram complexas e importantes teias geopolíticos e transnacionais, num contexto africano e mundial de Guerra-Fria e de rescaldo da cisão sino-soviética, que valerá a pena dissecar.

Pretende-se com esta conferência internacional assinalar os 50 anos decorridos desde esses acontecimentos transcendentais para a vida de territórios outrora colonizados por Portugal em África, nalguns dos quais (Guiné, Angola e Moçambique) foi necessário passar por devastadoras guerras de libertação/guerras coloniais. Essas lutas pela emancipação inscrevem-se como eventos conexos de uma longa história de resistência dos povos submetidos à exploração imperial, ao trabalho forçado, ao racismo e ao colonialismo. Como é sabido, os processos que levaram às independências geraram múltiplas dinâmicas e ramificações que, por um lado, ultrapassaram as simples fronteiras dos respetivos territórios concernidos; por outro, tais processos produziram interações interna e externamente com vários elementos e condicionalismos, combinando o contexto internacional da época com as demandas internas dos povos colonizados pela soberania política.

Neste sentido, as independências não devem ser interpretadas como acontecimentos históricos isolados, nem como eventos lineares e homogéneos. Há uma historicidade própria que carateriza os processos de independência referente a cada um dos territórios, processos esses marcados por complexidades de diversa ordem. Tanto assim é que não podemos separar as independências das lutas dos movimentos de libertação, do anti-colonialismo, das revoluções terceiro-mundistas, do anti-imperialismo, das lutas contra a ditadura Portuguesa, etc. Em suma, as independências resultaram das várias lutas levadas a cabo pelos movimentos de libertação em diferentes frentes. E as ações destes contribuíram para a revolução de 25 de Abril de 1974 e, por conseguinte, para a queda da ditadura em Portugal.

Chamada para comunicações

50 anos após esses processos históricos que levaram à emergência de novos estados-nação, esta conferência internacional pretende reflectir sobre as múltiplas dimensões – histórias, processos, legados e memórias – desses eventos independentistas que mudaram a configuração da política global do mundo da segunda metade do século XX. Neste sentido, apela-se a propostas de comunicações sobre tópicos como:

- Lutas pelas independências (conceitos, contextos políticos, culturais e sociais);

- Lutas pelas independências, anticolonialismo, anti-imperialismo e revoluções terceiro-mundistas;

- Solidariedade internacional com as colónias portuguesas e cruzamentos com outras lutas anticoloniais no contexto da Guerra Fria;

- Atores, militantes e organizações independentistas;

- Género, educação e mobilização popular nas lutas pelas independências;

- Artes, artivismo e manifestações culturais nas lutas pelas independências;

- Contributo das lutas pelas independências para o fim da ditadura portuguesa;

- Descolonização pós-25 de Abril de 1974;

- Construção dos novos estados-nação africanos e neocolonialismo;

- Heranças coloniais nos países africanos independentes e em Portugal;

- Guerras civis e transição democrática nos países africanos independentes;

- Construção da memória nos países africanos independentes e em Portugal.

Os resumos das apresentações (200 palavras), acompanhados por notas biográficas (250 palavras), devem ser enviados para: independencias50anos@gmail.com

Prazo para submissão: 15 de dezembro de 2024

Notificação de aceitação: 30 de janeiro de 2025

Línguas de trabalho: Português, Inglês e Francês.

>> Descarregar a Chamada para Comunicações (PT / FR / EN, PDF) <<

Palestrantes convidados/as:

Maria da Conceição Neto (Universidade Agostinho Neto)

Severino Elias Ngoenha (Universidade Eduardo Mondlane)

Comissão Organizadora:

Aurora Almada e Santos (IHC — NOVA FCSH / IN2PAST)

Julião Soares Sousa (CEIS 20 — Universidade de Coimbra)

Raquel Ribeiro (IHC — NOVA FCSH / IN2PAST)

Víctor Barros (IHC — NOVA FCSH / IN2PAST)

Comissão Científica:

Gabriel Fernandes (Universidade de Santiago)

Jean Martial Arséne Mbah (Investigador, Doutorado em História Contemporânea)

Jean-Michel Mabeko-Tali (Howard University)

Marçal de Menezes Paredes (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul)

Maria Nazaré de Ceita (Universidade de São Tomé)

Michel Cahen (Sciences Po Bordeaux)

Miguel Cardina (Universidade de Coimbra)

Odete Semedo (Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisa, Guiné-Bissau)

Pedro Aires Oliveira (IHC — NOVA FCSH / IN2PAST)

Teresa Cruz e Silva (Universidade Eduardo Mondlane)

Tempo

julho 17 (Quinta-feira) - 19 (Sábado)

Localização

Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa

Alameda da Universidade — Cidade Universitária — 1649-014 Lisboa

Organizador

Instituto de História Contemporânea — Universidade NOVA de Lisboa e CEIS20 - Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares — Universidade de Coimbra

Detalhes do Evento

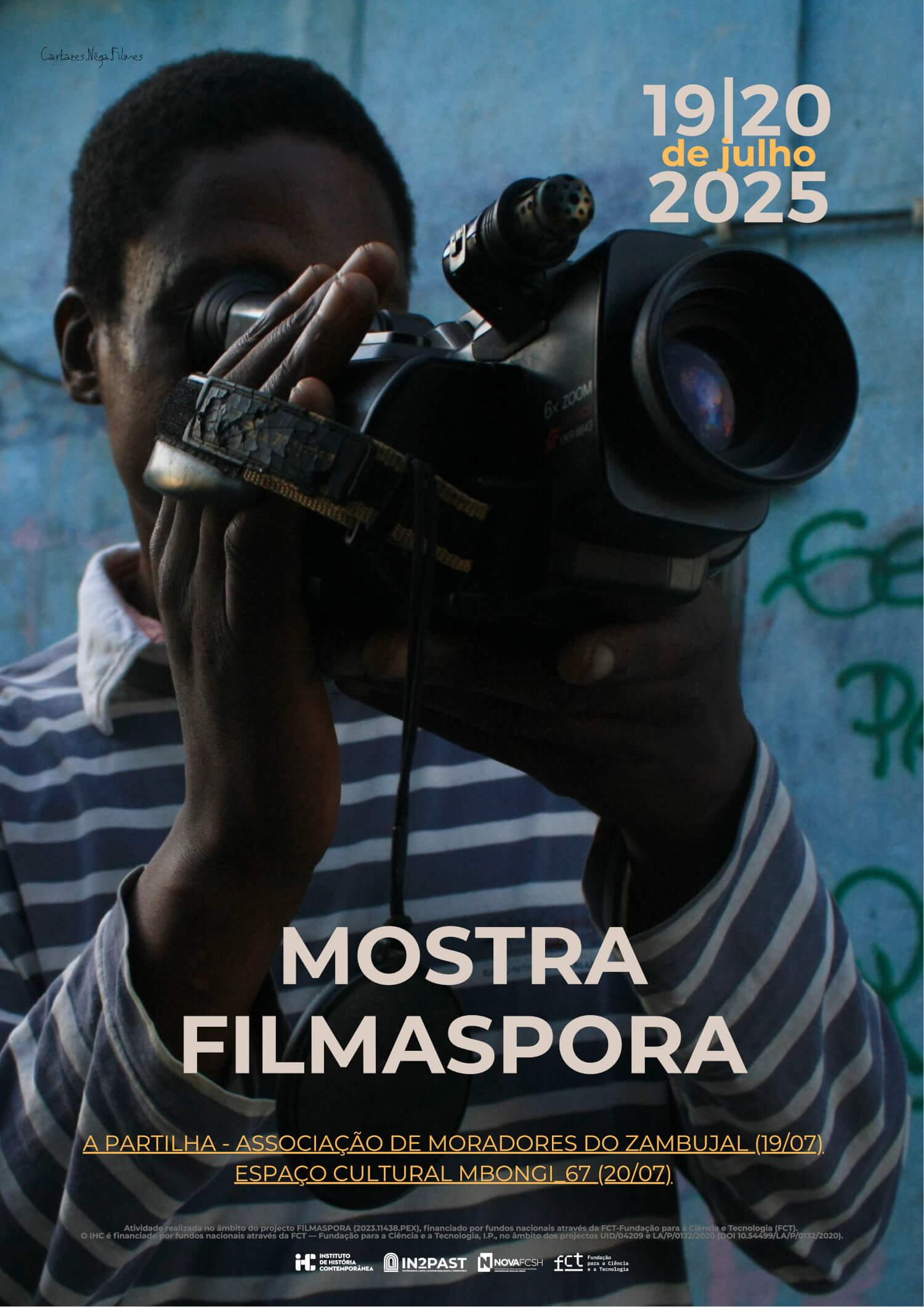

Mostra de filmes que promove o encontro entre produções da Linha de Sintra e obras realizadas no Bairro do Zambujal. Organizada pelo projecto FILMASPORA. Mostra

Ver mais

Detalhes do Evento

Mostra de filmes que promove o encontro entre produções da Linha de Sintra e obras realizadas no Bairro do Zambujal. Organizada pelo projecto FILMASPORA.

Mostra FILMASPORA

Nos dias 19 e 20 de Julho, a equipa do projecto FILMASPORA organiza uma mostra de filmes que promove o encontro entre produções da Linha de Sintra e obras realizadas no Bairro do Zambujal.

Junte-se a nós para dois dias de diálogo, partilha e cinema.

O projeto FILMASPORA tem como objectivo fomentar o intercâmbio cultural e audiovisual, aproximando comunidades através da exibição de curtas e médias-metragens que dão voz às vivências, expressões e narrativas locais.

Programa

19 de Julho

A Partilha — Associação de Moradores do Bairro do Zambujal, Loures, 21h

21h – HIP-HOP KRIOLO

21h30 – Enciclopédia Hip Hop Volume 1 (2016), de Uncle C

20 de Julho

Espaço Mbongi 67, Linha de Sintra, 16h

16h – Lisboa, Pódio de Quimeras (2021), de Welket bungué

16h30 – Cantores do Submundo (2012), de Fernando Moreira

>> Programa da mostra (PDF) <<

Tempo

19 (Sábado) 9:00 pm - 20 (Domingo) 6:00 pm

Localização

Loures e Sintra

Organizador

Instituto de História Contemporânea — Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade NOVA de Lisboacomunicacao.ihc@fcsh.unl.pt Avenida de Berna, 26C — 1069-061 Lisboa

Notícias

Quarta edição do Prémio Amílcar Cabral

Jul 17, 2025

Candidaturas abertas até 30 de Setembro

Projecto RESONANCE estuda performance no período revolucionário

Jul 16, 2025

RESONANCE é coordenado por Hélia Marçal

Manuel Loff recebe Medalha de Mérito do Porto

Jul 14, 2025

Foi uma das personalidades homenageadas pela Câmara Municipal do Porto